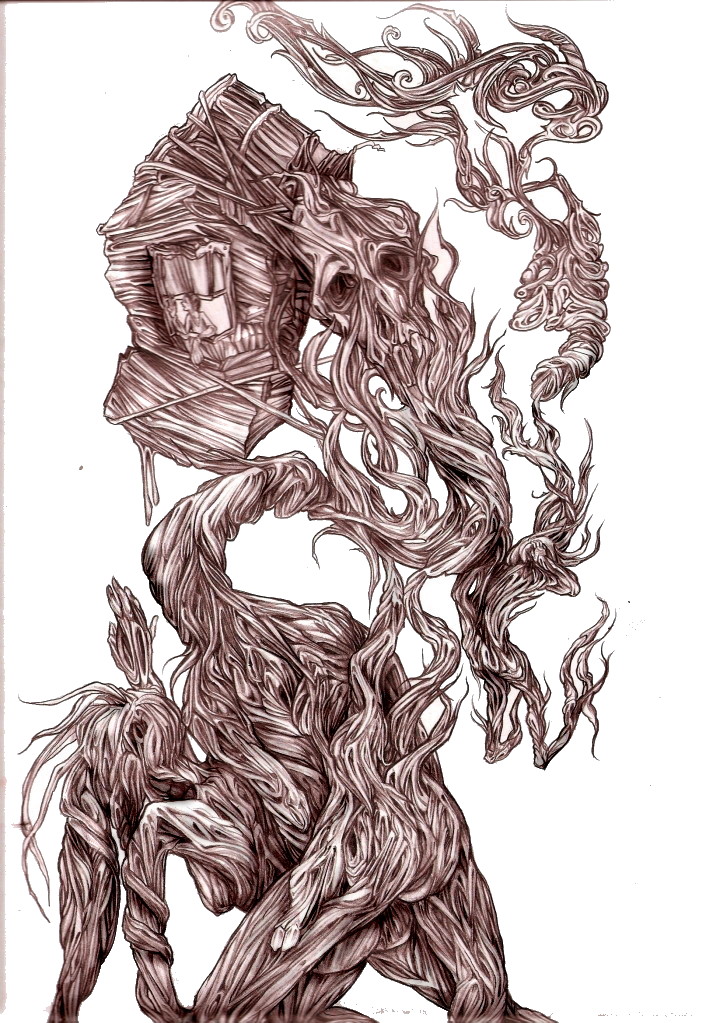

Bone window

I am coming through

in sin, bearing seed,

vertebrally, I stand

with structural faults,

held by blind nails

hiding the salt in the marrow.

I cruise through blue veins

with murderous intent,

through delicate cartilage

and mucous membrane,

to cup a hip or breast

I am sexed.

Carnival of Shivers

The Cure for What Ails You

One of the worst, or at least most difficult things about being gay and Muslim is that…well, you’re not really both gay and Muslim at the same time. At least, I haven’t been able to find that reconciliation in my own life just yet, and it’s frustrating, because I don’t think that sexual orientation should inevitably lead to a sense of spiritual emptiness. Of course, it’s complicated by many other things too. For example, I decided about a decade ago, that since I was going to Hell for being attracted to other men anyway, I didn’t really need to worry about following any of the tenets of Islam (fasting, praying, pilgrimage etc.). And tautologically, since I wasn’t performing any of those key activities, I was going to be damned anyway, so why not enjoy some booze and a quickie with some stranger (or several, depending on how much booze is involved)?

But this is about more than just alcohol. It’s actually way more about sex than anything else. Maybe that’s because all of the major faiths of the world have no shortage of verbiage on the topic; how to do it, when to do it, why to do it, with whom to do it…it’s actually remarkable. I’m not a religious scholar, but there seems to be an almost unhealthy obsession with regulating sexual activity. And in all fairness, there are some good reasons for this level of attention–overpopulation, abandonment, irresponsibility, societal dysfunction, etc.–but it’s all a little LCD (Lowest Common Denominator), isn’t it? I mean, the link is not a hard one to follow: all faiths recommend procreation within an environment for what, if one were in a particularly cynical mood, could be easily described as “Grow me some more of my cannon fodder, baby”. It makes sense: all faiths were, at one point in their respective existences, nascent and vulnerable. A great way to buttress a faith is with large numbers of believers, and who better to create and rear said believers than…well, other believers?

It would be very easy to turn this into an article about free love and polygamy and all sorts of theoretical conceits that really only worked for about 300 stoned hippies in the 1960s. The truth is that sex is something of a sacred act, partially due to indoctrination, and partially because for your traditional heterosexuals, it can have wide-ranging consequences. Unlooked-for pregnancies and all the drama they entail, STDs, emotional vulnerability (OK, so the last two can be shared by humankind as a whole)…all of these are very good reasons for people to think about what they’re sticking where, and with whom. For people to whom the idea of a spouse and children is effectively the only reason for being–to further grow their particular branch of a family tree, or just because it fulfils them (there are biological imperatives here too, and they should be recognised), it is difficult to even articulate, let alone acknowledge the concept of a life that finds happiness in the choice between stability and instability, in creating its own rules and strictures; the kind of happiness that comes from making their–our–own social bindings.

Unfortunately, there’s no real way to simultaneously embrace both freedom of thought and the strictures of organised religion. You can’t–for the purposes of illustration–combine blowjobs and prayers as a mutually inclusive lifestyle choice, not if you hold firm to the tenets of either behavioural mode. To me, that is where the frustration and the difficulty lie: you don’t really get to choose.

Well, you do, in a way. You can choose to believe that you are innately evil and an abomination and spend your life in a frenzy of apology to make up for being the aberration that your faith condemns you as–you struggle to overcome your nature, because that’s the test that God has placed in your path. You twist and warp who you are so that it’s in keeping with a book and rules laid down millennia before you had a say in anything, and because your parents or guardians made the choice of a faith on your behalf. You could also–a la Irshad Manji and Al-Fatiha–insist on carving out your own identity, but only insofar as it can co-exist with the strictures of your religion, which is a bit of a bastardisation of both without the satisfaction of either. Or you could accept yourself for who and what you are–realise that you just are a certain way and that while you have an ethical and moral obligation to behave appropriately for the society in which you live (no murder, rape, theft etc.), you also have an obligation to be honest and truthful to yourself.

See, not having or following faith doesn’t mean you have to behave like a raging tool. You can still respect your parents/elders, behave with decorum, treat other people well, follow the basic precepts of civilised conduct etc. Getting hammered on week-ends with your friends doesn’t make you a bad person. Nor does the fact that you don’t pray on a regular basis have to mean that you’re going to suffer in an after-life. For my part I refuse to believe that if I, as a good person, make a concerted effort to treat people fairly and well, to give back to my community inasmuch as I can, and generally live my life with a sense of caring…well, any religion that would, in the fact of that, condemn me for trying to find love with someone of my own biological gender, is a faith I’m better off without. I fail to see how my inability to pray–and I do this out of respect, because I don’t see the point in performing empty rituals blindly just as a contingency plan for Heaven–daily outweighs the fact that I give a hefty chunk of my pay-cheque to charity every month. After all, isn’t the point of damnation to punish you for what you’ve done wrong, rather than not done at all?

And as long as we’re talking about honesty, not a day goes by that I don’t secretly wish–just a little bit–that I were straight. Life would certainly be a lot easier. This is not to say that I’m unhappy with who I am. Au contraire, I find that my homosexuality has given me the kind of life experiences that I’d probably never have come across otherwise. But anyone who thinks that we homosexuals deliberately make a choice as to our lifestyles and willingly repudiate “normalcy” (highly over-rated anyway) has been mixing several kinds of prescription-only medicine. Let me make this simple: given the status quo in the world today, why would anyone choose to be queer?

Bride Denied: Media Coverage of Mukhtaran Mai

In early April, Mukhtar Mai, the Pakistani survivor of a tribal-ordered gang rape who prosecuted her rapists rather than accepting a tradition of suicide after rape, married her bodyguard, Nasir Abbas Gabol.

Scathing condemnations of the marriage came from Pakistani writers, women’s groups, and news outlets. While the circumstances under which she married are troubling, the way that Pakistani media has discussed the Mai and her marriage is equally troubling.

According to AFP, these are the facts: Nine years her junior, Gabol first proposed in 2007. When he was rejected he tried to kill himself with an overdose of sleeping pills. “The morning after he attempted suicide, his wife and parents met my parents but I still refused,” Mai said. Gabol then threatened to divorce his first wife, Shehla Kiran. Panicked at the prospect of enduring the stigma of divorce, Shehla sought to persuade Mai — who was married and divorced before her rape — to consent to becoming a second wife. … On Mai’s insistence, Gabol transferred ownership of his family house to his first wife, agreed to give her a plot of land and a monthly income — all designed to guarantee Shehla’s rights. In exchange, Mai tied the knot. But she has no intention of moving to her husband’s village, away from the hive of activity she has created here with the help of aid money.

These are the facts that the media agrees on. By most accounts, this seems like a measured, deliberate marriage, even if an unwanted one. But reading most media analyses, one would think either that Mai was as giddy as a school girl or a traitor to women’s rights.

The AFP article that I pulled all these facts from also paints Mai as a “gushing” bride who is living the “happily ever after” storyline: “Seven years after her ordeal, she may still be a pariah among illiterate and older women but her transformation from victim to queen of her own destiny is complete since becoming the second wife of Nasir Abbas Gabol.”

This completely contradicts an interview she gave to Mag The Weekly, an online Pakistani magazine, in which she said of Gabol’s proposals:

I knew that Nasir Abbas is a married man with five children. I was concerned about his wife and children and I kept arguing with my family members about the proposal. Then one day, Nasir sent his wife and children to our house. His wife forced me to marry her husband. Her behaviour was very strange to me. My siblings also forced me to accept the proposal. I finally gave up.

What romance! I can’t think of anything better than being coerced into becoming someone’s second wife by his reckless and selfish behavior! The AFP article inappropriately constructs Mai as some sort of Cinderella whose suffering has been rewarded by a knight in shining armor, not as a woman who has made deliberate moves to counter her suitor’s irresponsible threats.

AFP’s article, however falsely glittery, pales in comparison to the Pakistani reception. An article from the Inter Press Service, written by Zofeen Ebrahim, casts Mai in the role of fallen feminist hero.

Ebrahim writes, “Mai, who has fought a valiant, 7-year-old battle against tradition and patriarchy was suddenly no longer a role model and icon.” So now Mai’s feminist card gets revoked? The article makes it seems as if Mai’s hard work prosecuting her rapists has all been washed away with this marriage.

It also discounts the work she is currently doing. According to AFP:

Mai runs three schools — two for girls and one for boys — where around 1,000 children from poor families get an education. She heads a staff of 38, half of them teachers, the rest working in her office and welfare centres. They shelter female victims of violence who trek far and wide to seek refuge with Mai, organise seminars to boost awareness of rights, dispense legal aid and operate a mobile unit that reaches out to women in their communities.

Running schools for girls and education women about domestic violence and their rights? Not feminist at all!

Perhaps if Mai were to give all this work up and move in with her husband, I could understand the condemnations by Pakistani women and feminist groups. But Mai has stipulated that she’s not giving up her schools, her work, or her village. So what’s behind all these accusations of Mai’s feminist treason?

“Mukhtaran Mai has fallen from being a national heroine to a disappointment, even for the media,” asserts Karachi-based Najma Sadeque, a founding member of Shirkat Gah, a non-governmental organisation.

“One wishes she had not done it,” says Naeem Sadiq, a business consultant here who actively campaigns on pro-democracy issues.

Sadiq who considers Mai an “exceptionally brave woman” is concerned that her marriage sends a message that “she is promoting polygamy”.

That’s some serious hatorade. Sadiq and Sadeque fail to realize that Mai’s marriage happened the way it did because she is a role model, and is conscious of the messages she sends. Mai’s marriage contract, her conditions that guarantee herself divorce and land and a monthly allowance for Gabol’s first wife, and her commitment to her work and her village send a powerful message that a woman’s marriage does not have to be a submission, but can be a political and social tool.

In all of this condemnation, no one ever mentions Gabol’s irresponsible behavior (suicide, threatening to divorce his first wife, disrespecting Mai’s choice not to marry him). Sadeque says, “I think she shouldn’t have done it since it immediately puts the first wife in a secondary, dispensable and vulnerable position.” This statement completely glosses over the fact that it was Gabol that first put his wife in this position: it was his first wife who, worried over the fact that Gabol had threatened to divorce her because of Mai’s rejections, sought Mai’s acceptance.

Pak Tea House’s coverage, written by Aisha Fayyazi Sarwari, is the only outlet that brought up Gabol’s issues in a way that puts any culpability on him: “There are some troubling signs in this new relationship. One is that the groom, Mr. Gabol is an unstable character, younger and indelibly lacking in the maturity she possesses, and was a little too quick to commit suicide with sleeping pills when she turned him down in 2007.” Sarwari raises issues and concerns about Mai’s marriage without blaming her for them, unlike other outlets.

Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?

And by cowboys, I mean straight people.

When we conceived of Chay Magazine, we did not imagine that we would lack for content about heterosexual life – heterosexual love, heterosexual sexuality, marriage, divorce, dating, harassment. We were expecting all of these things. What’s more, we were really worried about finding enough content by or about anyone who wasn’t straight.

Gosh, we were wrong. People are coming at us left, right and centre writing about queer issues, about gender issues, about non-heteronormative love, sociology, health and spirituality. What Chay Magazine is sorely lacking, despite dogged dogging of writers we think could broaden the scope our publication, is a lot of writing about heterosexual sexuality.

We have some, obviously. But have a look at some of the comments, the links to which appear on the right hand sidebar on the homepage. Half of them are engaging with the queer-centred content. The other half are berating us or our writers, in polite or less-than-polite language, for talking about sex, talking about homosexuality as if it was real and positive, and bringing obscenity to society.

It seems to me that the only people really willing to put aside their shame, shyness and fear around the topic of sex and sexuality are people who are willing to engage non-heteronormative topics. With some notable exceptions, it seems that most people think that there’s nothing to talk about in heteronormative, straight sexuality.

Which is too bad. Because we were hoping that Chay Magazine would be a place to talk about domestic violence, loving relationships, marriage, children, clandestine dating, parental pressures, polygamy – any number of things that have to do with the sexuality of all Pakistanis, straight, gay, trans*, cis, bi, whatever.

So here at Chay, we commend and thank all our contributors who are willing to engage this topic, despite their own personal reservations, fears and the knowledge that they will receive great opposition in public. And we invite all those who are as yet silent to come and talk to us about, really honestly, anything they want.